"Danny Boy"

Lyrics set to an Ancient Irish melody

now called "Londonderry Air"

Recorded by Libera

at St. Patrick's Cathedral, Armagh

|

Oh, Danny boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling

From glen to glen, and down the mountain side.

The summer's gone, and all the roses falling,

It's you, It's you must go and I must bide.

But come ye back when summer's in the meadow,

Or when the valley's hushed and white with snow,

It's I'll be there in sunshine or in shadow,—

Oh, Danny boy, Oh Danny boy, I love you so!

|

But when ye come, and all the flowers are dying,

If I am dead, as dead I well may be,

Ye'll come and find the place where I am lying,

And kneel and say an Avé there for me.

And I shall hear, though soft you tread above me,

And all my grave will warmer, sweeter be,

For you will bend and tell me that you love me,

And I shall sleep in peace until you come to me! |

Like many people, I can trace my ancestors back to the 19th century and some to the 18th century. But unlike most people, I can also trace my ancestry back to the 5th century. There is a gap between the 5th and 18th centuries, but I know I have paternal Biggins ancestors who lived in far northern Ireland in the 5th century. They lived along the River Faughan in the barony of Tirkeeran. See: "From Tirkeeran to Kalamazoo," Newsletter of the Middlesex Genealogical Society, September 2022. Vol. XXXVIII, No. 3, p. 2.

Quotation from an ancient bard in The History of Ireland by Geoffrey Keating (1569-1644). Translated into English from the original Irish by John O'Mahony, 1857. |

I know this because of mutations in my Y-DNA. Only males have Y-DNA. Y-DNA is handed down from male to male, like surnames.

Mutations in my Y-DNA are shared with certain testers who can trace their ancestry on paper back to the 4th century. We know that, in the 5th century, our ancestor named Carthend lived in the Faughan River valley. The area became known as Tir-Keeran, the "land of Carthend." Saint Patrick founded seven churches in Tirkeeran. Maybe Patrick converted Carthend.

In some cases, Y-DNA can tell us who our ancestors descend from in the last one or two thousand years. This has happened for me. I share the Y-DNA of men having combination of surnames that ancient pedigrees trace back to The Three Collas, who emigrated from England to Ulster in the 4th century.

Z3008 is the name given to the Y-DNA of The Three Collas. It was discovered in 2013. It is a mutation called a SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism). Less reliable mutations had been discovered in 2006. Only males have Y-DNA.

Z3008 testers have been found to be descended from The Three Collas based on 20 matching surnames and two genealogies:

- 20 Matching Names. In October 2020, 232 out of 466 testers with R-Z3008 Y-DNA were found to have 20 surnames found in the ancient genealogy of The Three Collas. The 20 surnames, in order of prevalence, are: 53 McDonald, 43 McMahon, 23 McKenna, 17 Connolly, 17 Duffy, 12 McGuire, 8 Monaghan, 8 Hughes, 8 McQuillan, 7 Boylan, 5 Hart, 5 Kelly, 4 MacDougall, 4 Higgins, 4 McArdle, 3 Cooley, 3 Neal, 3 Larkin, 3 Carroll, 2 Devine. See: Two Matching Sets of 20 Names. (Surnames not found in the ancient genealogies, like Biggins/Beggan, also have Z3008 Y-DNA.)

- Two Genealogies. Nine Z3008 testers have connected their genealogies with ancient genealogies of The Three Collas: seven McDonalds and two McMahons. They happen to be among the two most common surnames.

- The seven McDonalds trace their ancestry back to Lt. Brian McDonald, born in 1645 in Arklow, County Wicklow, and then back to McDonnell of Antrim, Somerled of Argyle, Carthend, and Colla Uais. See: 43 Generations: Colla to McDonald.

- The two McMahons trace their ancestry back to Conn MacMahon of Killshanlish, who died in 1663, and then to Colla da Crioch. See: 50 Generations: Colla to McMahon.

Z3008 is a subset of Z3000. A Z3000 tree is available in two forms: Abridged and

Unabridged.

Colla Uais SNP Tree, with McDonald Genealogy

I share four SNPs with the seven McDonalds: Z3008, S953, ZZ13, and FT14481. Following is a SNP tree for Colla Uais, interspersed with the genealogy of the McDonald testers who can trace their ancestry back to Colla Uais. The division of the genealogy by SNP is somewhat arbitrary because the SNP dates are very rough estimates and dates are limited for many ancestors in the genealogy. Testers other than McDonald 1 testers have the McDonald genealogy starting back from the second preceding SNP. For example, a Biggins tester with the BY3164 SNP shares generation 1 to 7 of the McDonald genealogy, including Carthend who lived in the Faughan River valley. He is unlikely to share 9 and even less likely to share 8 and 9.

Colla Uais SNP Tree, with McDonald Genealogy

| Z3008 450 AD England

1. Colla Uais, fought in battle in 392 in Ulster

2. Erc

3. Carthend, lived in Tirkeeran on Faughan River

|

| S953 500 AD Tirkeeran

4. Muredach

5. Amalgad

|

F4142

550 AD

MacDougall

White |

Y9053

1600 AD

Østerud |

BY2869

1050 AD

Connolly |

ZZ13 600 AD

6. Aed Guaire

7. Colman Muccaid

8. Fergus: died in 668

|

BY24138

750 AD

Boylan |

FT14481 750 AD

9. Conal

10. Niad

11. Fergus

|

BY3164

1400 AD

FT17167

1400 AD

Beggan |

BY39827

1250 AD

McAuley

O'Hara |

BY103517

1400 AD

Larkin |

A945

1200 AD

BY43421

1750 AD

McGuire |

A938 850 AD

12. Goffrad: died in 853

|

| FT112238 900 AD

13. Maine

14. Niallgus

15. Suibhne

16. Meargagh (or Marcus)

17. Solamh (or Solomon)

18. Gille Adamnan

19. Gille Bride

20. Somerled: died in 1164

21. Reginald: born about 1148

22. Donald: died in 1249

23. Angus Mór: died in 1301

|

BY84773

1100 AD

King |

Martin |

| McDonald 1*

24. Alasdair Og: died 1308

25. Somerled (Sorley): died 1387

26. Marcus: died 1397 in Antrim

27. Charles Thurlough Mor: died 1435

28. John Carrogh; died 1466

29. Charles Og McDonald: died in 1503

30. John McDonald: died 1514

31. Charles Turlough McDonald: died 1522

32. Calvagh MacTurlough McDonald: died 1570

33. Hugh Buidhe McDonald: died 1618

34. Brian MacDonnell: died about 1635

35. Alexander MacDonnell died in 1683

36. Brian MacDonnell: emigrated

to America in 1689, died in 1707

BY3158 1700 AD Wicklow

37. Bryan II McDonald: born 1686

A14093 1750 AD Wicklow

|

McDonald 2

BY3249

1200 AD |

Unabridged Tree: The complete tree is at: Clan Colla Big Y SNP Tree

SNPs: SNPs are single nucleotide polymorphisms, or mutations, found on the Y chromosome and shared by a group of testers. Major SNPs are shown in the top part of the table. The very roughly-estimated year in which a SNP was born is shown in parentheses. Click on a SNP to see detail on Fanily Tree DNA Discover.

Collas: The Three Collas lived in Ulster in the fourth century. Descendants of the actual Colla brothers (Uais and Crioch, no Menn) are most likely those with the SNP Z3008. |

Surnames: Surnames with three or more testers are listed under the SNPs. Surnames in bold are said in ancient pedigrees to be descended from The Three Collas. See: Two Matching Sets of 20 Names. Many surnames in the ancient pedigrees are not here because they have not been tested, died out, or were included in a pedigree in error. The most populous name is McDonald.

*McDonald 1 includes seven McDonalds who trace their ancestry back to Lt. Brian McDonald (MacDonnell), McDonnell of Antrim, Somerled, and Colla Uais in 43 Generations: Colla to McDonald. |

Colla Uais from Colchester

This DNA is shared by testers with ancestral names that match names in ancient pedigrees of men descended from three Colla brothers who lived in the 4th century in a part of northern Ireland called Airghialla or Oriel. In 1998, Donald M. Schlegel, suggested in his article "The Origin of the Three Collas and the Fall of Emain" in the Clogher Record that the Three Collas were Romanized Britons from the Trinovantes, a celtic tribe from Colchester, the oldest recorded Roman town in England. They received military training from the Romans and eventually went to Ireland as mercenaries in the service of the King of Ireland.

Any genealogy that goes back 16 centuries is not going to be as solid as one that goes back two or three centuries. Nevertheless, we think the attempt is worthwhile. You can judge for yourself. The source for the pedigree is The Ancestors of the McDonalds of Somerset, by Donald M. Schlegel, 1998. Sources consulted by Schlegel include: Book of Ballymote (ca 1400), Book of Lecan (Early 1400s), Nat. Lib. Scot. MS 72.1.1 (1467), Monro (1549), Harleian MS 1425/190-191 (ca 1620), Annals of Clan Macnoise (1627), Geoffrey Keating (ca 1634), O'Clery (mid 1600s), and Book of Clanranald (ca 1715).

Carthend

Excerpt from The Ancestors of McDonalds of Somerset

by Donald M. Schlegel, pp. 10-13. Copyright 1998, used with permission.

Carthend

Pagan Life and Beliefs

The pagan Celts of Ireland lived in a world of fear, from which the loving God was far removed, and in which they were at the mercy of monstrous spirits and arbitrary, insubstantial reality. They were people bound by unreasoned custom and superstition, for they thought that the world was full of hidden "traps" that were triggered by the violation of taboos. The power of the kings was rivaled or even eclipsed by that of the priests, who were called druids. The druids officially ranked next to the kings in social standing, but they usually exercised paramount sway, for no undertaking of any moment was begun without their advice. They were skilled in astronomy and healing; they practiced sorcery in the seclusion of oak groves, where their doings were hidden from the common people; and, through the power that they exercised over the whole society, they imposed upon the common people.

The pagans adored a divine being (though not necessarily always and everywhere the same one) to whom they offered sacrifices and from whom they sought all blessings, temporal and eternal. Crom Cruach, the "prince" of all idols in Ireland, stood on Magh Slecht, the "plain of prostration" near the Gothard River, now in the barony of Tullyhaw, County Cavan. This "plain" was a limestone ridge some 400 by 85 yards in extent. From the base of its eastern escarpment issues a strong, clear, and rapid spring, as if a river-god dwelt within his rocky halls beneath the ridge and poured forth this perennial fountain. The pagan kings and nobility offered firstlings of animals and other sacrifices to the idol. One source says that it was embossed with silver and gold and had twelve bronze statues ranged around it.

The pagan Irish theology embraced belief in the immortality of the soul, the transmigration of the soul, and a heaven and a hell.

Their heaven had perennial spring, immortal youth, and unending sunshine. Gentle breezes fanned it; pleasant rivers watered it; trees alive with celestial music and bowed with flowers and fruit sheltered it. There the wicked ceased to trouble and the weary found rest; the inhabitants, strangers to anything that could give pain, enjoyed an unending scene of calm festivity and gladness.

Their hell was a dark and dismal region where no ray of light ever penetrated. It was infested with every animal of vile and venomous kind. Serpents hissed and stung; lions roared; wolves devoured. The cold was so intense that the bodies of the wicked, of a gross nature on account of their crimes, might have frozen to death, had death been possible for them.1

The pagan Irish year was punctuated by four great feasts. The year began on November 1 with the feast of Samhain. At this juncture of the old and new years, it was said the otherworld became visible and spirits roamed the world of men. (This was the origin of the celebration of Halloween.) Livestock was rounded up and sorted for slaughter or breeding at this time. Imbolc or Oímelc was celebrated on February 1, the time of the lactation of ewes. Its place in the Irish year was later taken by the feast of St. Brigid of Kildare. Beltaine was held on May 1, when the Mordháil or great assembly was held at Uisneach in today's County Meath, at which goods, wares, and jewels were exchanged. Sacrifices to the god Bel were associated with it and the druids lit two fires between which cattle were driven to protect them from disease. All fires were extinguished and new fire was brought to each hearth from the Bel-fire. This was also the time of the annual beginning of pasturing in the open. The fifteen-day festival of Lughnasad, honoring the god Lug, began on August 1 and was connected with the harvest.

Establishment of Tir-Keeran

In the generations following the three Collas, the claimed high-kingship of Ireland stayed it the family of Muiredach Tireach, passing to his grandson Niall Noighiallach around the year 400.

It was perhaps in the 420s that three sons of Néill Noighiallach named Conall, Eoghan, and Enda conquered from the Cruithne or Bolgraidhe (i.e. the western Fir-Bolg, and perhaps their Ulaid overlords) the far northwest of Ireland, the lands surrounding the Foyle and extending east to the Bann. There they set up the Kingdom of Ailech, named for its chief fortress, which is located on a hilltop between the Foyle and the Swilly. The fortress has battered stone walls, guard-chambers, and terracing on the inside of the walls, with steps to give access to this terracing and to the wall-top.

The sons and grandsons of Colla Uais apparently assisted the sons of Niall in this conquest and moved north with them. Colla's son Erc in one record is called "ri sliab a tuaid," king of the northern mountain.2 His son Carthend was given land on the east side of the Foyle, the valley of the River Faughan, then called Dulo Ocheni but later named Tir-Keeran (Carthend's land) after him, and still today bearing that name as a barony. To the east, the Ciannachta (a Leinster tribe that also assisted the Uí Niall) settled in the valley of the River Roe, called Glen Given. The coast eastward from Ard-Eolairg (Magilligan) remained in possession of poor Cruithne or Picts; they had a fortress (Dun Cruithne) in Ard-Eolairg. Carthend's nephew Dochartach and his brothers were given lands southeast of Ailech at Ard-Sratha; their descendants were the Ui Fiacarh Ard-Sratha. Far to the east, on the west side of the Bann Valley were settled Carthend's cousins, grandsons of Fiachra Tort, whose descendants were the Fir Lí and Uí Tuirtri (from whom descended the ÓFlynns of County Antrim, along with the ÓFlanagans). Each of these territories was a tuath with its own minor king.

Of Carthend himself we know only that, born into a pagan world, he subscribed to its marriage practices; he had six sons by one or more wives and another six by bondswomen.

The Conversion of the Irish

According to the oldest traditions, it was in 432 that Patrick, the Christian former captive of an Irish chieftain, came to Ireland to bring the Faith to the people he had learned to love. The piety of Patrick no doubt impressed the Irish, for he always traveled on foot, slept on the bare ground, and recited the Psalter and a number of hymns and prayers each day. Patrick worked among the Irish of Ulster. A biography written some three or four centuries after his death claims that he came into northwest Ulster about the year 441 and evangelized the sons of Niall Noighiallach, then crossed the Foyle into Tir-Keeran, then visited the rest of the northern Airghialla. This story reflects the Irish political geography of its own time, not Patrick's. What has become clear after decades of study and debate is that Patrick was the missionary especially of the Ulaid. He founded his episcopal see at Armagh, perhaps in the 440s, while the nearby site named Emain Macha was still the symbolic center of the Ulaid, where their annual assembly or óenach was held. It was after Armagh was founded and probably in the 460s that the Airghialla, under the leadership of the Uí Niall of Meath, defeated the Ulaid once again and drove them across Glen Righe. St. Patrick withdrew with the Ulaid to Saul in County Down and Armagh was placed under the control of Sechnall, the missionary bishop of Meath. Armagh was thirteen years in his hands before Patrick was able to reclaim it.

It is not clear when or by whom the northern Airghialla were evangelized, but that it was by St. Patrick as claimed by his early biographers is not impossible. The old chronology of his life is not accepted by some today, for if it be correct he must have been nearly 95 years old at the time of his death on March 17, 493. As Warren H. Carroll has pointed out, however, he would only have been "somewhat younger than St. John the Evangelist, Bishop St. Simeon of Jerusalem, St. Anthony of the desert, Bishop Ossius of Cordoba, and Bishop Acacius of Beroea when they died, to mention only some particularly well-known and well-attested instances of longevity in this period."3

St. Patrick supposedly founded seven churches in Tir-Keeran, seemingly corresponding to the seven parishes of the historical period. One of his lives names them: Domnach Dola, Domnach Senliss, Domnach Dari, Domnach Senchue, Domnach Min-cluane, Domnach Cati, and Both-Domnach. (The word Domnach indicates a stone church, and often one supposedly founded by the Apostle himself.) The first of these was near the Foyle. The last, Both-Domnach, may have been not in the valley, but across the Sperrin Mountains in County Tyrone, at the place now called Badoney in the territory of the Ui Fiachra Ard-Sratha.

There is some evidence that Ireland did not embrace Christianity as completely as Patrick's biographers claimed; paganism persisted in some areas during his life and for many decades, at least, after his death.

By any measure, however, the conversion of the Irish to Christianity was remarkable. "We cannot but admire the omnipotence of God, and the power of His grace, in the rapid conversion of this idolatrous nation. So sudden a change can only be attributed to Him Who has the power of softening the most callous hearts; for it can be said with truth, that no other nation in the Christian world received with so much joy the knowledge of the kingdom of God, and the faith in Jesus Christ. Nothing can be found to equal the zeal with which the new converts lent their aid to St. Patrick, in breaking down their idols, demolishing their temples, and building churches. We may likewise add, that no other nation has preserved its faith with more fortitude and courage, during a persecution of two centuries."4

Ireland "was not compelled to the Christian culture, as were the German barbarians of the Continent, by arms. No Charlemagne with his Gallic armies forced it tardily to accept baptism. It was not savage like the Germanies; it was therefore under no necessity to go to school. It was not a morass of shifting tribes; it was a nation. But in a most exceptional fashion, though already possessed, and perhaps because so possessed, of a high pagan culture of its own, it accepted within the lifetime of a man, and by spiritual influences alone, the whole spirit of the Creed. The civilization of the Roman West was accepted by Ireland, not as a command nor as an influence, but as a discovery."5

NOTES

- M'Kenna, Diocese of Clogher, I/237-238; O'Malley, 223; Healy, The Life and Writings of St. Patrick, pp 184-185

- Book of Leinster 333.c.15; see O'Brien, 415

- Carroll, Warren, The Building of Christendom; Front Royal: Christendom College Press, 1987; p. 124

- MacGeoghegan, 1844 transl., p. 147

- Hilaire Belloc, Europe and the Faith; New York: The Paulist Press, 1920

|

I bind to myself to-day,

Christ with me, Christ before me,

Christ behind me, Christ within me,

Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ at my right, Christ at my left,

Christ in the fort,

Christ in the chariot-seat,

Christ in the mighty stern.

- 8th verse of Saint Patrick's Breastplate

|

Tirkeeran and Tullygarvey

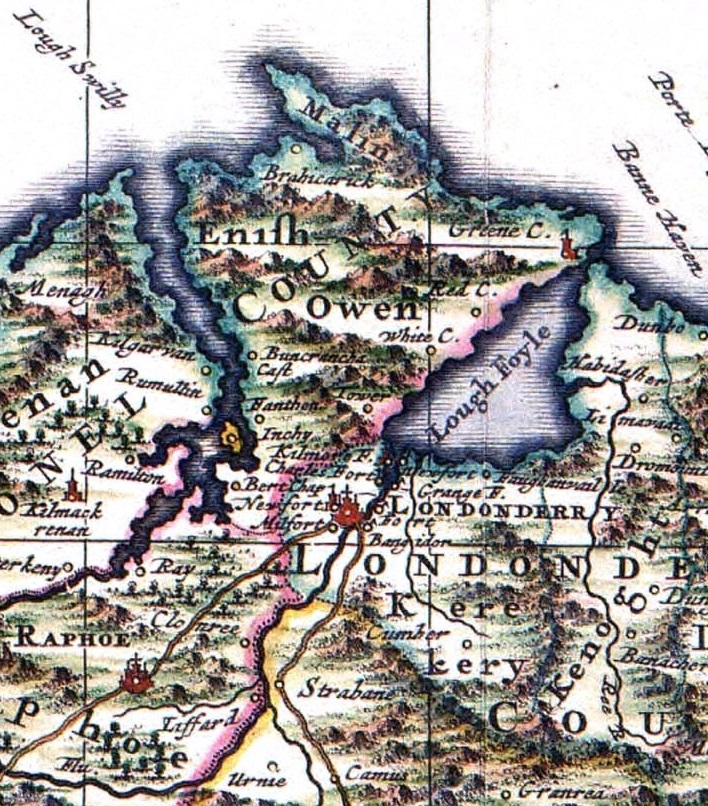

Below is an excerpt from a 1899 map showing counties and baronies of Airghialla inhabited by descendants of The Three Collas. In earlier times, baronies were called cantreds and tuaths.

At the top of the map is Tirkeeran in County Londonderry (Derry), where Carthend, grandson of Colla Uais, settled in the Faughan River valley in the 5th century. At the bottom is Tullygarvey in County Cavan, where Hugh and Ann Cusack Beggan lived in the townland of Drumgill in the 19th century. Carthend, Hugh, and Ann are most likely my ancestors. Drumgill is 80 miles south of the Faughan River valley.

In the Griffith's Valuation property survey of 1848-64, the biggest concentration of Biggins/Beggan households is in two contiguous baronies: Clankelly in County Fermanagh, Dartree in County Monaghan, and Tullygarvey in County Cavan. The largest town in this area is Clones, County Monaghan. See: Biggins/Beggan Irish Roots.

Tirkeeran

The name Tirkeeran comes from the Irish Tír Mhic Caoirthinn, which means land of Carthend.

About 12% of those who are descended from The Three Collas based on Y chromosome testing are descended from Carthend. Their surnames are

Connolly, Boylan, Biggins/Beggan, McAuley, O'Hara, Larkin, McGuire, McDonald, Reilly, King,

Martin, and Østerud. McDonald is the largest and includes seven who have genealogies that do back to Colla Uais. They all have or are predicted to have the S953 SNP, which is roughly estimated to have been born in 500 AD.

Tirkeeran has an area of 149 square miles. The western border is the River Foyle. The northern border is Lough Foyle. The eastern border id the barony of Keenaght. The southern border is County Tyrone. The southeastern border with Tyrone is formed by the Sperrin Mountains.

The Londonderry Line of the Northern Ireland Railways starts in Londonderry on the Tirkeeran side of the River Foyle and runs north along Lough Foyle, then east south east to Belfast. The track gauge of 5 ft. 3 in., called Irish guage in Ireland and broad gauge in Australia and Brazil.

Below is an excerpt from a 1837 map showing the Barony of Tirkeeran in County Londonderry, where Carthend, grandson of Colla Uais, settled.

River Faughan

The River Faughan is 29.5 miles long. It rises on Sawel Mountain, north of Park and flows northwestwards through Claudy, crossing the A6 west of Drumahoe. It flows northwards on the eastern edge of Derry city, being bridged by the A2 between Campsey and Strathfoyle. The Faughan enters Lough Foyle east of Coolkeeragh power station.

The River Faughan flows through Tirkeeran in a northwesterly direction and eventually discharges into Lough Foyle. The river flows through a valley of glacial origin with large deposits of sand and gravel present throughout the catchment. The river rises in central County Londonderry on the western slopes of the Sperrins mountain range.

According to Queen's University Belfast, the ancient semi-natural woodland along the Faughan valley includes Ness Wood, Ervey Wood and Bonds Glen, all Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSIs) designated for their priority woodland habitats and associated rare woodland species.

The picturesque Faughan Valley Woodlands are made up of a collection of enchanting ancient woods, including Oaks Wood, Brackfield Wood, Red Brae Wood, Killaloo Wood, Burntollet Wood and Brackfield Bawn Wood. The Faughan Valley Woodlands are rich in flora and home to an abundance of rare and wonderful wildlife. These unique species rely on the ancient woodland here in order to survive. Otters, Atlantic salmon and lamprey swim in the Faughan River, while pine marten scurry in the trees overhead .Source: Woodland Trust.

Tirkeeran Park

While the barony of Tirkeeran still exists and bears that name, baronies are not commonly referred to now. There is, however, a street named Tirkeeran in the village and townland of Maydown, in the barony of Tirkeeran. It is 500 feet from the River Faughan.

On the left is a short street named Tirkeeran Park in the village and townland of Maydown. 500 feet east is the River Faughan. 600 feet west (not shown) is marshy Enagh Lough with its man-made Green Island. One mile northwest is Strathfoyle on the River Foyle. On the A2, 3 miles southwest is the bridge over the River Foyle in Londonderry. |

Tirkeeran Townland and Road

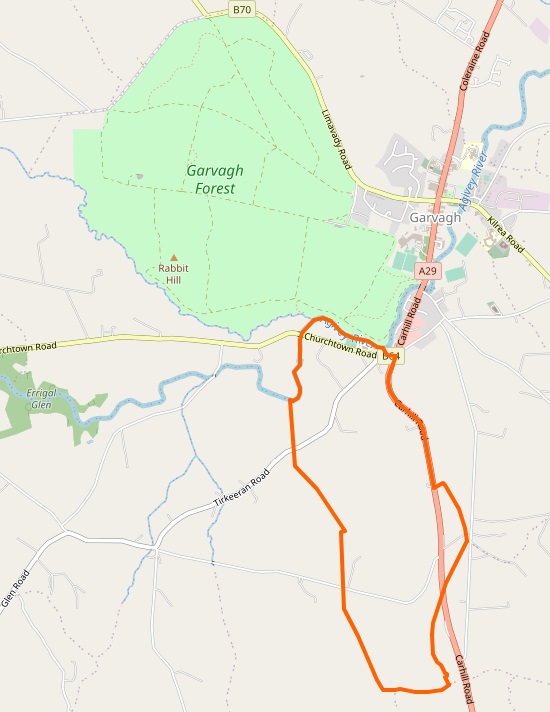

Two baronies east of Tirkeeran is the barony of Coleraine. There is a townland by the name of Tirkeeran. It's area is 277.8 acres. It is just south of the town of Garvagh. It is 18 miles east of the barony of Tirkeeran. It is six miles from the River Bann, the eastern border of Coleraine. The Bann was inhabited by the Fir Lí, cousins of Carthend.

Tirkeeran Townland and Road just south of the village of Garvagh in the barony of Coleraine. |

Diocese of Derry

The Diocese of Derry serves the catholic congregation of 51 parishes across almost all of County Derry, parts of County Tyrone and County Donegal, and a very small area across the River Bann in County Antrim.

From Our Story - by Fr John R Walsh:

|

Saint Patrick brought Christianity to the peoples who lived in the extreme north-west of Ireland in the fifth century. Patrick gives us no information that can link him with any specific place within what is now the diocese of Derry or, indeed, within Ireland. All Patrick tells us about his mission field is that he directed his steps to "the most remote places, beyond which no man dwells".

The earliest surviving written identification of Patrick with places in Ireland is to be found in Bishop Tírechán's Brief Account. This document was penned some two centuries after the Saint's mission. When dealing with the area now known as the diocese of Derry, Tírechán has his hero found the church of Donaghmore in the Finn Valley. He has the saint proceed to Glentogher in Inishowen and thence into the Faughan Valley where he is said to have established seven churches. The Brief Account then has Patrick visit Ardstraw and consecrate Mac Erca as bishop there before founding the church of Tamlaghtard at Magilligan. From Tamlaghtard Patrick is said to have gone to work in the territory immediately west of the Lower Bann before crossing the river to evangelise the area around Coleraine.

Having won over the local king Patrick seems often to have placed a bishop over the tuath or small kingdom. But Patrick's imposition of a diocesan structure on his mission territory was foreign to his converts. In the sixth century the church became monastic in character. Great monasteries with networks of daughter houses under them mirrored the secular world where over-kings dominated groups of tuatha. Gradually the Irish church became monastic with abbots rather than bishops as the chief churchmen. In the north-west of Ireland the main monastic founders in the sixth century were: Saint Eugene of Ardstraw, now the principal patron of the diocese of Derry, Saint Columba of Derry, Saint Lurach of Maghera, Saint Comgall of Bangor and Camus-juxta-Bann and Saint Canice of Drumachose. The monasteries were centres of learning.

A number of medieval treasures associated with people and places in the present diocese are considered parts of the artistic heritage of Ireland. Chief among these are: the psalter known as the Cathach, the oldest surviving Irish manuscript, now in the Royal Irish Academy, and the shrine, now in the National Museum of Ireland, made in the eleventh century to enclose it; the famous book-reliquary, associated with the parish of Clonmany, known as the Miosach of Columba; the Crosses at Fahan, Carndonagh, Carrowmore, Cloncha and Cooley, all on Inishowen; Saint Mura's Bell, now in the Wallace Collection in London; Saint Patrick's Bell and the shrine which housed it, both in the National Museum; handbells linked to the parishes of Culdaff, Drumragh, Termonamongan, Badoney Lower, Donagh, Cappagh, and Clooney; the Fahan Christmatory, a tiny bronze vase for holy oil, dating from around 1100 and now in the National Museum of Ireland; the Mortuary House at Banagher; and the Maghera Lintel.

|

Parish of Claudy

|

History of Saint Patrick's Old Church, Claudy: Cumber Upper and Learmount was the original name of the parish - the addition Claudy (a stony beach) is only a few centuries old. Archbishop Colton journeying throughout the diocese in 1397 came across a new parish Church on the old site in the townland of Cumber, near where Glenrandal and the Faughan rivers meet. Today the ruins of a church stand on the site where Dr Colton beheld one. The ancient tradition is that Saint Patrick built seven churches along the Faughan and one of these he erected at Cumber. Further down the Faughan there was another church. Poston's house in Kilcatten now stands on the site of this church. |

From Parish of Claudy.

Tirkeeran Cheese

Tirkeeran Cheese, made by Dart Mountain Cheese, 26 Tamnagh Road in the village of Park, near the village of Claudy. Established in June 2010 by Julie Hickey. On the River Faughan in the foothills of the Sperrin Mountains. Dart Mountain is on the southeastern border of Tirkeeran, along with Sawel and Meenard. Its peak is 2,031 feet above sea level, the 5th highest peak in the Sperrins.

Long aged pasteurised cows Milk cheese, extra hard.

A fantastic and unique cheese.

Use as an alternative to Parmesan. Perfect for grating over pastas and risotto.

Won Bronze at the UK & Irish Artisan cheese Awards 2018.

Cartin.com

Edward Cartin of Belfast, Northern Ireland, has a website devoted to Carthend and the surname Cartin: Cartin.com.

Tirkeeran Townland, County Donegal

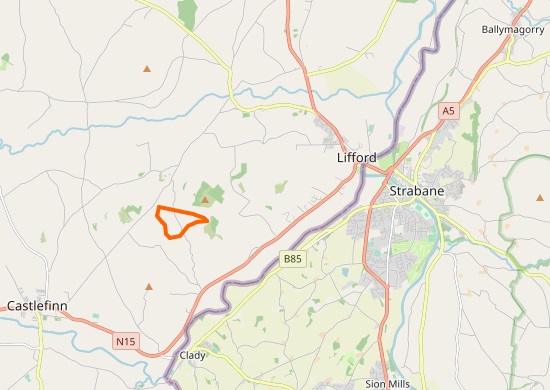

About 10 miles south of the barony of Tirkeeran, north of Strabane, the River Foyle is formed by the confluence of the River Finn and the River Mourne. Two miles west of Strabane, in County Donegal, is the Townland of Tirkeeran.

The locale was home to descendants of Colla Uais as far back as the fourth century. With the arrival of Saint Patrick, a mission established a church in the area near Castlefin, and having visited the Grianán Aileach for the conversion of Owen, returned along the River Foyle, establishing a further church at Leckpatrick (the name means 'the flagstone of St. Patrick') in Ballymagorry.

Tirkeeran Townland, County Donegal, two miles west of Strabane, County Tyrone. |

Grianan of Aileach

On the Inishowen peninsula in County Donegal is the Grianan of Aileach, a ringfort that served as the royal seat of the Ailech, overlords of Carthend and his descendants. The ringfort is 15 miles from the River Faughan. The wall is about 15 feet thick and 16 feet high. Inside are three terraces, which are linked by steps, and two long passages within it. Originally, there would have been buildings inside the ringfort. Just outside it are the remains of a well and a burial mound.

Grianan of Aileach scenic view looking westerly. The enclosed area is 77 feet in diameter. In the upper right is the walkway to the island of Inch (Inis) in Lough Swilly. Photo by Mark McGaughey. Source Grianan of Aileach |

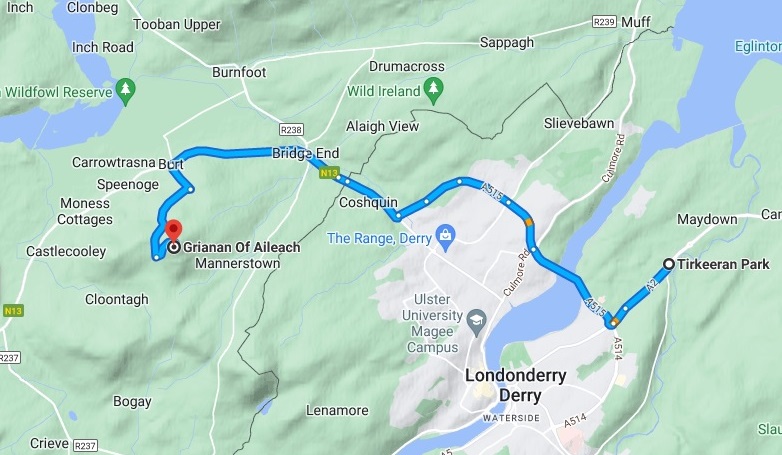

10 mile trip over the River Foyle from Grianan of Aileach to Tirkeeran Park, by the River Faughan. The Lough Swilly is upper left. |

1689 Map of Inishowen and Tirkeeran

Excerpt from 1689 map of Ireland showing Inishowen and Tirkeeran. The River Faughan can be seen flowing north from Cumber into Lough Foyle. Published by Nicolaes Visscher II. Source History of Ireland |

250 miles above the Earth on Saint Patrick's Day

Northwesterly view of far northern Ireland from the International Space Station, 250 miles above the Earth on Saint Patrick's Day, 2013. At the top is the Atlantic Ocean. Lough Swilly is top left. River Foyle is right. Between the two rivers is the Inishowen Peninsula. Tirkeeran is center, below the River Foyle and Lough Foyle. The River Faughan is shown faintly starting at the bottom center, and flowing up through Tirkeeran into Lough Foyle near the mouth of the River Foyle. At top center right is Malin Head, the most northerly point of mainland Ireland. Five nautical miles right of Malin Head is Inishtrahull, the most northerly island of Ireland. Barely visible above Inishtrahull is the most northerly landfall of Ireland, a rock called the Tor Beg. Photo by Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield. Source Lough Swilly |

I bind to myself to-day,

The power of Heaven,

The light of the Sun,

The whiteness of Snow,

The force of Fire,

The flashing of Lightning,

The velocity of Wind,

The depth of the Sea,

The stability of the Earth,

The hardness of Rocks.

- 4th verse of Saint Patrick's Breastplate

|

|

The River Faughan, Tirkeeran

The River Faughan, Tirkeeran The River Faughan, Tirkeeran

The River Faughan, Tirkeeran